Artistic expression is as ancient as humanity itself. Throughout history, humans have sought ways to communicate beyond the spoken word and written text. Among the myriad subjects of such expression, cats have held a unique place in various cultures, with some embracing these feline companions much earlier than others. This is reflected in the visual and figurative art that portrays them. In this first article of our series about cat art, we’ll delve into how cats have been represented in art throughout human history, beginning with the earliest known depictions from ancient civilizations. Let’s embark on this journey through time to uncover the European and Anatolian artistic legacy of cats.

Paleolithic Europe (ca. 40,000 BC – 10,000 BC)

German Lion-Man figurine (40,000 BC – 32,000 BC)

One of the oldest figurative works of art in the world shows only the head of a large relative of our favorite animal. The Lion-Man Figurine with a lion head on a human body is one of the earliest known depictions of a somewhat feline creature. The exact age of this artifact varies according to different sources.

It’s about 31 centimeters (12 inches) tall, made of mammoth ivory, and was found in the Hohlenstein-Stadel cave in Germany. Because it did not have many other things from everyday life in it, the assumption is that this place had been reserved for ritualistic ceremonies. It could indicate early human beliefs in the power of animals and the desire to embody or invoke their strengths.1 It’s possible that this sculpture shows a shaman or a mythical creature.2

The discovery of the Lion-Man was groundbreaking as it pushed back the known date of figurative sculpture and complex symbolic thinking in early human culture. The piece is held at the Ulm Museum in Germany, where it is a highlight of their prehistoric collection and continues to be an object of intrigue and study for archaeologists and art historians.2

Alongside the Lion-Man, there have been other remarkable prehistoric finds from the same region, including various animal figurines that date back to the Upper Paleolithic period, among which are representations of cave lions which were common in the fauna of that period.3

Apart from intriguing figures like these, paleolithic art extends further into the captivating world of wall paintings, revealing another dimension of prehistoric artistic expression.

French Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc cave paintings (ca. 36,000 BC – 30,000)

In 1994, an extraordinary site was discovered in the Ardèche river valley, France, known as the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave. This cave is adorned with an extensive array of animal depictions. Prominently featured are big cats such as cave lions and leopards.4

Within this cave, the “Alcove of the Lions,” stands out as a remarkable section where the paintings create the illusion of lions emerging from the rock’s crevices. These depictions offer a raw and direct representation of the Paleolithic environment, providing a glimpse into the everyday sights and experiences of our earliest ancestors. Here, scenes of cave lions and other animals capture aspects of nature integral to their daily lives.5

As we move from the vivid depictions of wild animals in the Chauvet Cave, our journey takes us next to Çatalhöyük. Here, the artistic focus shifts to more divine scenes, reflecting the transition of human societies toward a more settled way of life.

Neolithic Anatolia (ca. 10,000 BC – 2,200 BC)

Turkish Çatalhöyük Mother Goddess (ca. 7,500-6,200 BCE)

The “Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük,” a remarkable sculpture discovered at the Çatalhöyük archaeological site in modern-day Turkey, is a vivid representation of Neolithic artistry. This baked-clay, nude female figure is substantial in size, especially when compared to other artifacts from the site. She is depicted in a seated position, exuding an aura of corpulence and fertility that has led many to believe she represents a Mother Goddess. The statue, dating back to approximately 6000 BC, is notable for its unique design: the arms of the throne on which she sits terminate in feline heads, possibly lionesses, leopards, or panthers, evoking a “Mistress of Animals” motif. These animalistic features add a layer of mystique and power to the figure, suggesting her dominion over the natural world.6

Currently housed in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara, Turkey, the “Seated Woman of Çatalhöyük” is often compared to other prehistoric figurines, such as the Venus of Willendorf, due to its emphasis on fertility and feminine form. Mellaart’s interpretation of the figure as a deity of fertility worshipped by the Neolithic inhabitants of Çatalhöyük adds to the intrigue and importance of this artifact in understanding early human civilizations.6

Even though no depictions of our beloved house cat have been found yet, as we move from Neolithic Anatolia to the Minoan Civilization, we witness an artistic evolution from simple representations, supported by natural observations, to complex, mythological elements.

Minoan Civilization (3,000 BC – 1,100 BC)

Minoan is the term for the earliest advanced civilization in the Aegean region, centered on the island of Crete, famous for its elaborate palaces and sophisticated art.

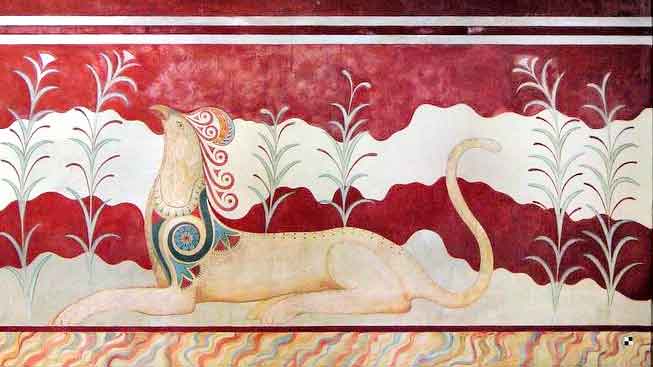

Cretan griffin fresco (1,700 BC – 1,450 BC)

The fresco at Knossos depicts two griffins, mythical creatures with the bodies of lions and the heads of eagles, positioned on either side of what is believed to be a royal throne. Their presence, in a state of repose, suggests a protective role, indicating the significance of griffins in Minoan culture as symbols of power and guardianship. Often they symbolized strength, bravery, and protection.7

The artistic style of the fresco, with its clear lines and stylized form, reflects the aesthetic preferences of the time, showcasing an interest in combining animal elements to create figures of mythological importance. This depiction of griffins, common in the art of the Eastern Mediterranean, speaks to the broader cultural and mythological exchanges in the region. The fresco’s location in the Knossos complex points to its possible role in ceremonial or royal contexts, offering a glimpse into how such mythical creatures were integrated into the everyday life and beliefs of the Minoans.

It seems like lions – and sometimes only their body features – were shared in artistic expression in different civilizations. What seems to be predominant in these pieces of art is that the lion stands as a symbol of power, maybe nobility, or protection.

Mycenaean Greece (ca. 1,600 BC – 1,100 BC)

Mycenaean refers to an ancient civilization centered on the Greek mainland, flourishing in the Late Bronze Age, known for its majestic palaces, rich tombs, and significant influence on classical Greek culture.

Greek lion’s head vessel (1,600 BC – 1,100 BC)

Unearthed from the storied soil of one of the Mycenae’s circular tombs, the Gold Rhyton in the shape of a lion’s head stands as a testament to the sophistication of the Late Bronze Age, circa 1,600 BC.

Preserved within the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, this exquisite piece showcases the Mycenaean civilization’s mastery in metalwork and their predilection for lion symbolism, which denoted strength and regality. The rhyton’s form suggests its sacred role in pouring rituals, offering us a glimpse into the ceremonial practices that wove through the fabric of Mycenaean society, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural heritage of the Aegean region.

Moreover, the era frequently showcased lions alongside divine figures, potentially alluding to the goddess Hera, weaving a narrative of religious symbolism and reverence into their artistry.

Early Iron Age Europe (800 BC – 400 BC)

Etruscan cauldron from Cerveteri (675 BC – 650 BC)

Etruria was an ancient region in central Italy, inhabited by the Etruscan civilization, renowned for its rich culture and significant influence on the development of Roman society.

Crafted from a single sheet of hammered bronze, this half-spherical vessel boasts five outward-facing lion protomes – lion’s heads – each affixed with riveted nails. It was found in the famous Regolini-Galassi-Grave in Cerveteri, and not just a cooking vessel, but a symbol of opulence, its design influenced by Oriental and Greek style.

In this Cerveteri grave, alongside a cauldron, other fascinating items surfaced, each adorned with big cat imagery, such as a belt, a bowl, and even a throne, hinting at the Etruscans’ admiration for these majestic creatures.

As we edge closer to the Common Era, we also get closer to the highlight: one of the earliest European depictions of a domesticated cat. Yet, let’s take a moment to delve into Greek mythology, as our next item beautifully narrates one of its classic tales which we can’t ignore.

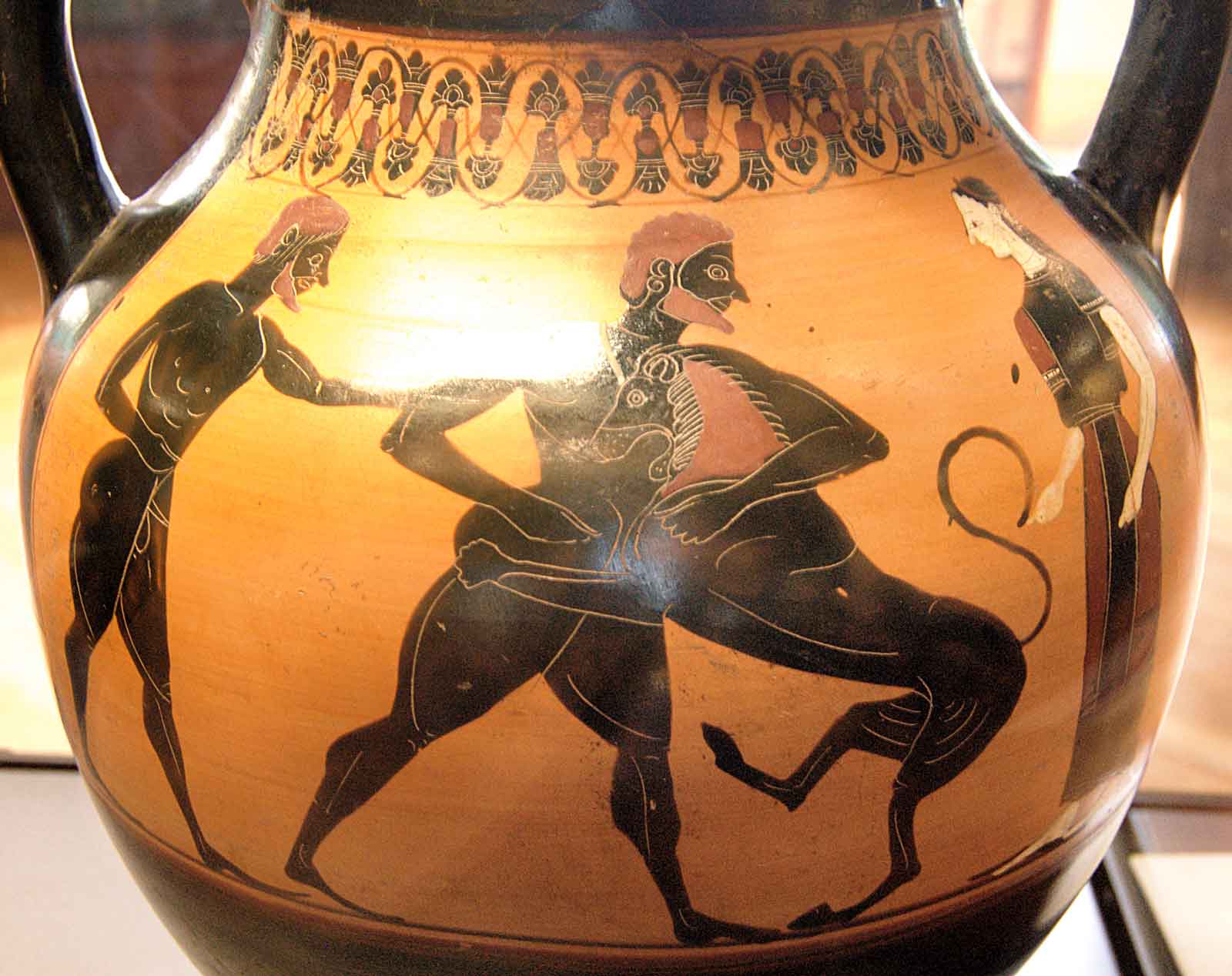

Greek neck-amphora (540 BC – 530 BC)

This neck-amphora intricately depicts Hercules’ first labor, assigned to him as penance for the grievous crime of murdering his family. Tasked with defeating the Nemean lion, he discovered the beast’s hide was impervious to his arrows, a revelation that intensified the challenge.

The amphora vividly captures this intense struggle, showcasing Hercules’ strength and pragmatism. More than just a depiction of myth, this scene encapsulates the essence of confronting seemingly insurmountable odds. Hercules’ ultimate victory over the lion is not just a display of brute force; it symbolizes a deeper journey of redemption, reflecting the enduring human themes of resilience, resourcefulness, and the unyielding courage to face tremendous trials.

Leaving behind the legendary Hercules, a hero of Greek lore, we now turn to the mystical world of the Celts. Much like the Greeks, the Celts revered their own symbols of strength and valor. This admiration is beautifully encapsulated in our next artifact: the Celtic lion cauldron, a masterpiece that blends the Celtic reverence for majestic creatures with artistic influences from across Europe.

Celtic lion cauldron (ca. 530 BC)

We return to today’s Germany, more precisely Baden-Württemberg. In Hochdorf Chieftain’s Grave, a richly-furnished burial chamber, regarded as the “Tutankhamun of the Celts” was discovered. Among the found items was a remarkably big cauldron that was originally adorned with three Greek lion motifs. A celtic artist deliberately decided to replace one of those with his own artistic version of a lion. According to the curator of the exhibition, this shows the Celts dealt with the influence from the south at the time. According to him, this speaks for the great self-confidence of the Celtic elite.9

Advancing from the Etruscan cauldron in our timeline, we return to Etruria with excitement for the long-anticipated reveal of the domestic cat in ancient art! This moment marks a delightful highlight in our journey, as we finally unveil the presence of our favorite animal in the rich mosaic of ancient artistic expression.

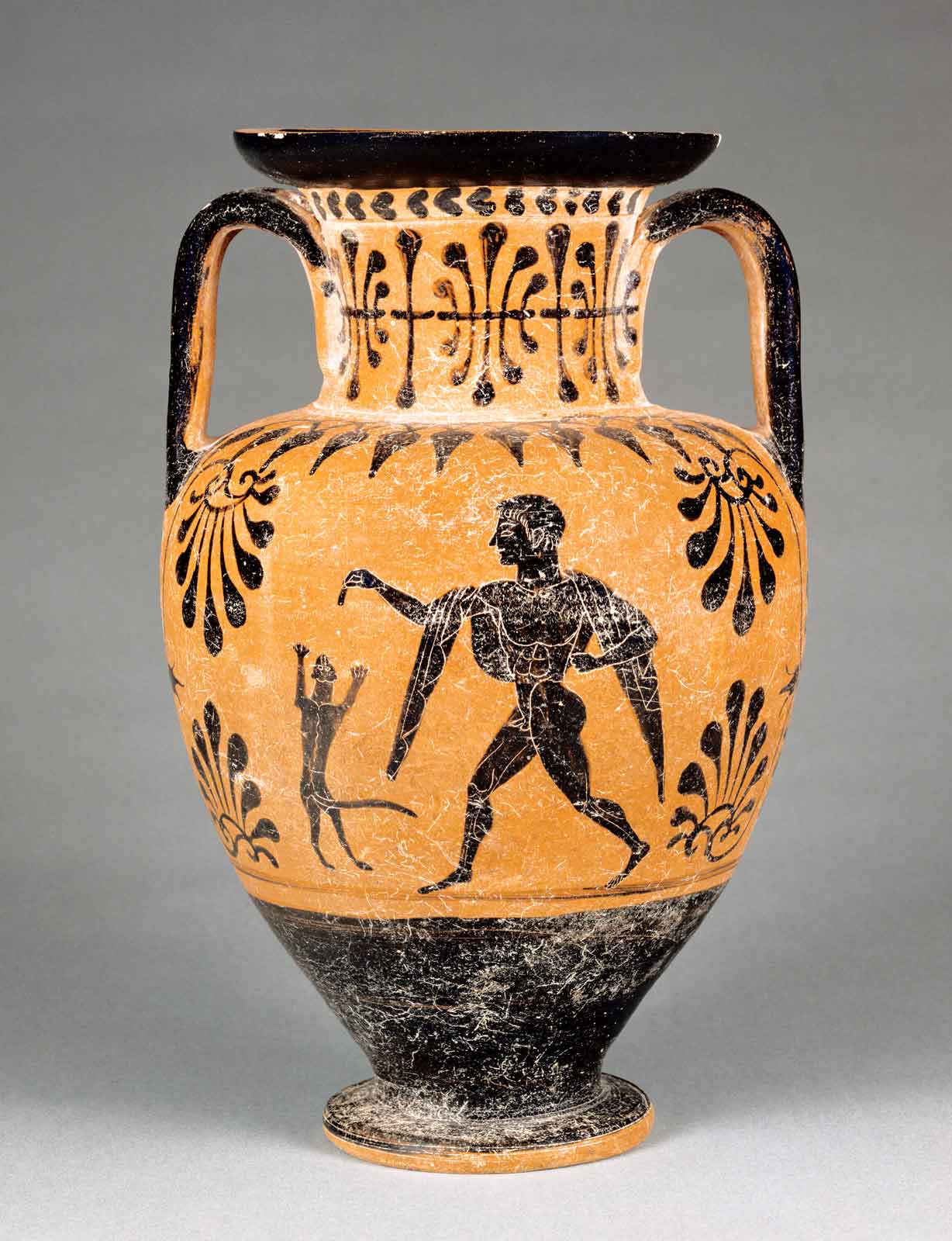

Etruscan neck-amphora (ca. 490 BC)

Finally, the domesticated cat makes its appearance. This terracotta amphora showcases a remarkable tableau: a bare young man is extending a piece of food to an eager, long-tailed cat. The feline is illustrated in a side view with her face turned to us, her forelegs outstretched in mid-leap, eager to claim her snack.

Within Etruscan art, representations of big cats and domestic cats as companions are relatively common. However, this particular depiction of a playful moment with a cat is an unusual find, sharing more in common with the Greek artistic narrative than with the Etruscan.10 The social life with cats is further chronicled in other Etruscan art from around this time, like in the tomb of Triclinium (ca. 470 BC) and a funerary urn from Chiusi (ca. 500 BC), where they are portrayed in domestic settings, lurking under tables and couches at banquets.11

That’s not all yet, folks!

Although evidence suggests that cat domestication occurred in Europe as early as the Neolithic period, artistic representations of these feline companions are sparse in European art history. While domestic cats featured prominently in artworks elsewhere, their presence in European art was notably less frequent.

Due to that, we turn our focus to Egyptian art next, a realm where cats held a significantly more esteemed position, revered not just as companions but as symbols of divine and everyday life. We invite you to join us in exploring the rich and diverse depictions of cats in Egyptian art, where they truly come into their own, celebrated for their grace, and revered for their mystique.